NachDenkSeiten – Die kritische Website

Titel: Low wages in Germany and the European imbalance problem

Datum: 4. September 2013 um 9:29 Uhr

Rubrik: Arbeitsmarkt und Arbeitsmarktpolitik, Ungleichheit, Armut, Reichtum, Wirtschaftspolitik und Konjunktur

Verantwortlich: Wolfgang Lieb

Germany has been achieving export surpluses year by year, with few exceptions, since the 1950s. Prior to the introduction of the euro there was a regularly recurring need for imbalances in foreign trade to be corrected through upward revaluation of the deutschmark. The introduction of the euro meant exchange-rate adjustments within the eurozone were no longer available as a corrective measure. Also, the German export industry is benefiting in trade outside the eurozone from the lack of serious pressure to revalue the euro upwards, a consequence of the substantial number of eurozone nations recording import surpluses.

Protected thus inside the eurozone from revaluation, Germany’s competitive position has been further enhanced since the late 1990s as a result of below-average wage increases relative to other eurozone countries, which in effect amounts to an internal devaluation. This in turn led to a rise in German export surpluses, which by 2012 were equivalent to about 6.5% of the German gross national product: in other words, over a mere three-year period Germany is forced to invest about 20% of its GNP overseas. German surpluses are matched by corresponding deficits in other eurozone countries. Currently, the German economy finds itself in an exceptional situation in Europe as a result of its highly developed international trade links. The openness of the economy (total of exports and imports as a proportion of GNP) in Germany, France, Spain and Italy was rated in 1995 at about 50%. But in 2008 the figure for Germany reached approx. 90%, against a rise to only 60% in the other countries…

Ein Beitrag von Gerhard Bosch, Geschäftsführender Direktor Institut Arbeit und Qualifikation Universität Duisburg-Essen

- A misdiagnosis becomes prevailing opinion

Germany has been achieving export surpluses year by year, with few exceptions, since the 1950s. Prior to the introduction of the euro there was a regularly recurring need for imbalances in foreign trade to be corrected through upward revaluation of the deutschmark. The introduction of the euro meant exchange-rate adjustments within the eurozone were no longer available as a corrective measure. Also, the German export industry is benefiting in trade outside the eurozone from the lack of serious pressure to revalue the euro upwards, a consequence of the substantial number of eurozone nations recording import surpluses.

Protected thus inside the eurozone from revaluation, Germany’s competitive position has been further enhanced since the late 1990s as a result of below-average wage increases relative to other eurozone countries, which in effect amounts to an internal devaluation. This in turn led to a rise in German export surpluses, which by 2012 were equivalent to about 6.5% of the German gross national product: in other words, over a mere three-year period Germany is forced to invest about 20% of its GNP overseas. German surpluses are matched by corresponding deficits in other eurozone countries. Currently, the German economy finds itself in an exceptional situation in Europe as a result of its highly developed international trade links. The openness of the economy (total of exports and imports as a proportion of GNP) in Germany, France, Spain and Italy was rated in 1995 at about 50%. But in 2008 the figure for Germany reached approx. 90%, against a rise to only 60% in the other countries Joebges et al. (2010: 6).One of the paradoxes of the economic policy debate in Germany is that the most serious weaknesses are perceived to be in precisely those areas in which Germany is particularly strong, while the strengthening of domestic demand has disappeared from the agenda. For 20 years now, German economic policy has been driven by a one-sided concentration on exports and the aspiration to improve the competitiveness of German industry. The politically powerful employers’ associations are dominated by those representing manufacturing industry, where the aim is to enhance global market share by keeping wages low. A large-scale media campaign mounted by the ‘Initiative Neue Soziale Marktwirtschaft’ (New Social Market Economy Initiative) – which has been funded since 2000 by the employer organisations in the metalworking and electrical industries – has successfully propagated the view that Germany, for all its low wage increases and large export surpluses, suffers from high labour costs and inflexible labour market regulations, and is consequently uncompetitive.

Those who subscribed to this view included the first Red-Green coalition. The Hartz legislation of 2004 was aimed at giving Germany a low-wage sector. By reducing unemployment pay – previously means-tested – for the long-term unemployed to the lower social benefit level, and by re-setting the ‘reasonableness’ criteria, the Hartz acts stepped up pressure on the unemployed to accept work at as much as 30% below the going rate for their locality. Deregulation of temporary agency work and of the so-called mini-jobs[1] made it possible to replace employees on standard contracts with new recruits on precarious contracts. In the case of temporary agency work, contracts ceased to be time-limited, and a new mechanism involving wage agreements enabled employers to sidestep the principle that temporary staff would have equal pay with the hiring company’s regular employees. As for ‘mini-jobs’, the income threshold was raised, mini-jobs could now be treated as second jobs, and the cap on hours worked per week was lifted, enabling wage rates to be reduced. The legislation’s political acceptability relied on the assertion that low-skilled employees with low productivity would be those to benefit most from the low-wage sector.

- The low-wage sector in Germany

Since the end of the 1990s, German wages have risen less than those in the rest of the EU. One principal reason for this is the rapid expansion of the low-wage sector, which was under way before the Hartz Acts. The share of low-wage workers (less than 2/3 of the median hourly wage) rose from 17.7% in 1995 to 23.1% of all workers in 2010. The number of low-wage workers increased from 5.6 million in 1995 to 7.9 million in 2010. One particularity of the German low-wage sector is its marked downward dispersion, since there is no minimum wage to prevent very low wages. In 2010, 6.8 million workers were paid less than the minimum wage of 8.50 euros demanded by the German Trade Union Federation, while 2.5 million actually earned even less than 6.00 euros per hour Kalina/Weinkopf (2012).

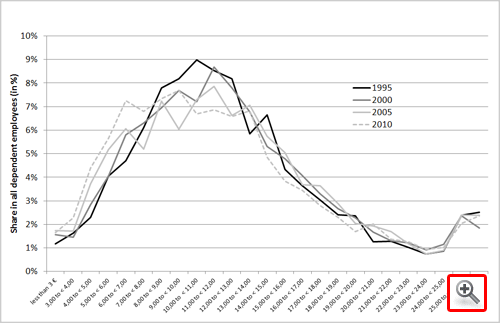

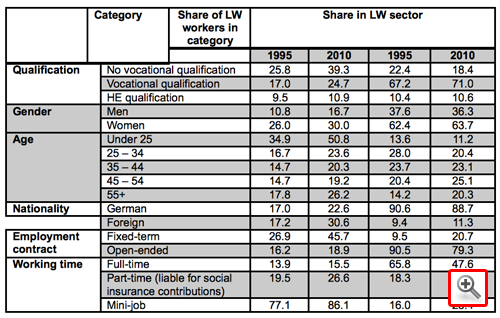

Virtually all the growth in absolute terms took place in West Germany, i.e. in areas traditionally protected by high levels of adherence to collective agreements. Examination of the evolution of the inflation-adjusted wage distribution since 1995 shows that the concentration of wages around the mid-point of the wage distribution is crumbling and many previously well-paid activities are sliding downwards (Figure 1). Low-wage work is not equally distributed among all employees. In 2010, those particularly affected by low wages were younger employees under 25 (50.8%), those on fixed-term contracts (45.7%), those without vocational training (39.3%), women (30.0%) and foreigners (31.9%) (Table 1). Because of the variable size of these employee categories, a distinction must be made between the impact on individual groups and the composition of the low-wage working population. Thus in 2010, 30% of female employees were paid low wages, but they accounted for almost two thirds (63.7%) of all low-paid workers (Table 1). One particularity of the German low-wage sector compared to the US is the low share of employees without a vocational qualification. Around 80% of people in the sector have a vocational or higher education qualification Bosch/Weinkopf (2008). The Hartz Acts’ aim of improving the employment chances of low-skill workers has not been fulfilled.

Figure 1: Distribution of hourly pay, Germany, adjusted for inflation (base = 1995)

Source: SOEP 2012, calculations by the IAQ, Thorsten Kalina

Table 1: Share of low-wage work and share of low-wage sector by employee category (Germany, all dependent employees, excl. school pupils, students and pensioners, in %)

* < two thirds of the median hourly rate of pay Source: SOEP 2010, calculations by the IAQ (Thorsten Kalina)

- Factors causing the expansion of low-wage work

The expansion of the low-wage sector began around 10 years before the Hartz Acts. The causes were changes in the behaviour of employers, who took advantage of high unemployment to quit employers’ associations and cease to be bound by collective agreements, and the opening up of many previously public services (post, railways, local transport etc.) to private providers who were not bound by collective agreement and competed with state-owned companies by engaging in wage dumping.

The Hartz Acts did not set this process in motion but prevented low-wage work from being reduced in the strong upturn from 2005 onwards. The two deregulated employment forms, temporary agency work and mini-jobs, have gained considerably in importance. The number of temporary agency workers rose from 300,000 in 2003 to around 900,000 in 2011, while over the same period the number of people employed in mini-jobs rose from around 5.5 million to 7.5 million. Among employees in mini-jobs, the share of low-wage workers was 86% in 2010 (Table 2); according to another survey, it was around two thirds for temporary agency workers. The high share of low-wage work among mini-jobbers can be explained primarily by the fact that employees in these jobs are generally, and in contravention of the European directive on the equal treatment of part-time workers, paid less than other part-timers. As far as temporary agency workers are concerned, the equal pay principle of the European directive on temporary work has been abrogated by collective agreements that amount to wage dumping concluded by the employer-friendly Christian trade union that has virtually no members.

The increase in low-wage work was supposed to make it easier for unemployed individuals to enter the labour market and to improve the employment chances of low-skill workers. In the mid-1990s, the German labour market was still being praised by the OECD for the good opportunities for advancement it offered low earners OECD (1996). That has now fundamentally changed. More recent investigations show that low-wage work is becoming increasingly entrenched. Kalina (2012) shows that the chances of advancement declined over the long period between 1975/6 and 2005/6. Mosthaf et al. (2011) note that only about one in every seven full-time workers who were low paid in 1998/9 was able to leave the low-wage sector by 2007.

- Deregulating the labour market has had no effect on employment levels

Coverage by collective agreement, which was around 80% prior to 1990, had declined by 2010 to 60% in West Germany and to 48% in East Germany. Autonomous wage-setting by the social partners is obviously no longer functioning. In many small and medium-sized enterprises and service industries, wages are determined unilaterally by employers, since collective agreements are not in force and works councils have not been set up.

As a result, the trade unions have reconsidered their rejection of state intervention in the wage-setting process and since the Hartz Acts have been campaigning for the introduction of minimum wages. Industry minimum wages have now been agreed with employers’ associations in 12 industries and have been declared generally binding by the Federal Government. The effects of minimum wages on pay levels and employment have been investigated in eight industries, in some cases using a difference in differences estimation. No negative employment effects were observed Bosch/Weinkopf (2012). However, a trend change towards a reduction in low-wage employment has not yet been instigated since the largest low-wage sectors, such as retailing and hotels and catering, do not have industry minimum wages. Attempts to introduce a national minimum wage and reform the Collective Bargaining Act to make it easier to declare industry agreements generally binding have so far been dashed on the rocks of federal government opposition.

The most contentious effects of the Hartz Acts are those on employment levels. Their positive employment effects are often explained with the higher outflows from unemployment since 2005. However, since inflows into unemployment have increased at the same time, despite the economic upturn, flows between employment and unemployment have increased. The reason for the increased flows in the economic upturn is the increased use of fixed-term contracts and temporary agency work, which often lead only to short periods of employment.

The Hartz-legislation came into force just as Germany was coming out of a deep recession. In the subsequent upturn, there was a sharp cyclical increase in employment. If the Hartz Acts did indeed influence this positive employment trend, then either the upturn must have been more employment–intensive as a result of better matching processes or the upturn was accelerated by the Hartz Acts. Horn/Herzog-Stein (2012) have compared the employment intensity of three economic cycles (1999/Q1 – 2001/Q1, 2005/Q2 – 2008/Q1 and 2009/Q2 until the current end point). In the first upturn, employment intensity (i.e. the percentage increase in the level of gainful employment when GDP rises by 1%) was 0.43% and in the two subsequent upturns it was just 0.35% and 0.39% respectively. Thus in fact the employment intensity tended to weaken after the Hartz Acts. The two upturns after they came into force were almost wholly driven by exports. The Hartz Acts had a damping effect on the evolution of wages; this effect was concentrated primarily in the service sector and ruined domestic demand and also demand for imports but had little effect on the export economy. Domestic demand was additionally curbed by public investment cuts. Net public investment in Germany has been negative for years. The consequent deterioration of the infrastructure has an adverse effect on future growth.

- Germany shares the responsibility of stimulating European economic growth

Thus the reasons for the favourable evolution of employment in Germany in recent years are not to be found in the Hartz Acts. They are the result of German manufacturing industry’s specialisation, over many years, in high-quality products, driven by a rapid pace of innovation, above-average investment in R&D and a good vocational training system. Moreover, the German product portfolio, with its emphasis on capital goods and cars, was well matched to the sharply increasing demand from the BRICS and other developing countries, which meant that the German economy was not wholly dependent on the European market. The Hartz Acts enabled the country, even in the strong upturn of 2005 to 2008, to continue its policy of internal devaluation within the Eurozone by means of below-average wage increases and unit wage costs relative to other Eurozone countries Stein/ Stephan/ Zwiener (2012). Since domestic demand and, consequently, imports as well did not keep pace with the growth in exports, trade imbalances within the Eurozone increased which is one of the principal reasons for the Euro crisis. Thus the impact of the Hartz Acts has a European dimension.

German economic policy continues to be characterised by its excessive focus on exports. As a way of dealing with the euro crisis, the German federal government advises other countries to introduce their own labour market reforms on the model of the Hartz Acts. This policy, however, cannot be applied at will to other countries, since only by abolishing the laws of mathematics would be it possible for all countries to have export surpluses.

Indisputably, the Southern European nations need to improve their competitiveness. But the crisis engulfing the euro can only be overcome if Germany, the strongest economy in Europe, takes on responsibility for generating growth. And there are good suggestions to tackle that. One is that the system of remuneration in Germany must be restored to health by introducing a minimum wage and strengthening existing wage agreements; another is to increase public investment in Germany, preferably under the aegis of a European investment programme.

Further reading

- Bosch, G. / Weinkopf, C. (eds.) (2008), Low-wage work in Germany, New York: Russell Sage Foundation.

- Bosch, G. / Weinkopf, C. (2012), Wirkungen der Mindestlohnregelungen in acht Branchen, Expertise im Auftrag der FES, Bonn (Effects of minimum-wage regulations in eight sectors. Expert report commissioned by FES, Bonn)

- Horn, G. A. / Herzog-Stein, A. (2012), “Erwerbstätigenrekord dank guter Konjunktur und hoher interner Flexibilität“ (Record employment figures owed to upswing and high internal flexibility), Wirtschaftsdienst, no. 3, pp. 151 -155

- Joebges, H. / Logeay, C. / Stephan, S. / Zwiener, R. (2010), “Deutschlands Exportüberschüsse gehen zu Lasten der Beschäftigten“ (Germany’s export surpluses are being paid for by the workforce), WISO Diskurs, pp. 1-35.

- Kalina, T. (2012), Niedriglohnbeschäftigte in der Sackgasse ? – Was die Segmentationstheorie zum Verständnis des Niedriglohnsektors in Deutschland beitragen kann (Low-wage workers at a dead-end? How segmentation theory can contribute to understanding the low-wage sector in Germany). Diss. Duisburg, Univ. DU-E.

- Mosthaf, A. / Schnabel, C. / Stephani, J. (2010), Low-wage careers: are there dead-end firms and dead-end jobs? (Universität Erlangen, Nürnberg, Lehrstuhl für Arbeitsmarkt- und Regionalpolitik. Diskussionspapiere, 66), Nürnberg.

- OECD (1996), Employment outlook, Paris.

- Stein, U. / Stephan, S. / Zwiener, R. (2012), Zu schwache deutsche Arbeitskostenentwicklung belastet Europäische Währungsunion und soziale Sicherung, Arbeits- und Lohnstückkosten in 2011 und im 1. Halbjahr 2012 (Weak German labour costs development is putting strain on European Monetary Union and social security. Labour and unit wage costs in 2011 and first half 2012). Reihe IMK Report, Nr. 77.

Hinweis: Der Beitrag erscheint auch in “Restoring Shared Prosperity: A Policy Agenda from Leading Keynesian Economists”, edited by Thomas Palley and Gustav Horn, CreateSpace.com, forthcoming.

Wir danken für die Erlaubnis zur Wiedergabe.

[«1] Minijobs are jobs carrying a maximum monthly wage of 450€. Those holding them are exempt from tax and other deductions. Employers are required to make a flat-rate 30% contribution. Under European and German legislation, holders of mini-jobs are entitled to the same pay for the same work and also to paid holidays, including statutory holidays, and paid sick leave.

Hauptadresse: http://www.nachdenkseiten.de/

Artikel-Adresse: http://www.nachdenkseiten.de/?p=18499